Second Zoom Session

Dialog 2: Topological Lacan

With Don Kunze and ChatGPT

Sunday 23 July 2023 • 12:00 noon (EST) New York • 5:00pm (GMT) London • 6:00pm Central Europe • 8:30pm Tehran

In this second zoom, there will be no formal presentation and minimal screen-shares. Rather, Don Kunze asks you to review his short essay, the transcript of his interview with ChatGPT on the question of aphasia, and any materials you may have at hand relevant to Lacan’s topology.

This mostly-conversation zoom focuses on Lacan’s insistence that while logic means structure, structure means topology. And, with this most visual of visual thinkers, who never ceased to divvy out diagrams, manifest mathemes, scatter schemas, and punctuate with poinçons, there would seem to be no getting around his insistence that topology is basic to psychoanalysis.

But, many do.

Although Lacan is explicit about where his topology comes from (“projective geometry” not the graph theory of the Königsberg Bridge Problem), how its represented (by fundamental polygons, not logical squares), and what it’s good for (everything!), Lacanians have been reticent if not terrified to engage the mathematics of Pappus, Desargues, Pascal, Plücker, Gauss, Riemann, Klein, and Möbius.

This session shall not be punitive or prosthetic. Rather it will focus on examples where the most entrenched skeptics may demonstrate to themselves the validity and utility of Projective Geometry. Iraj Ghoochani and Kunze have even taken topology to the unimagined frontiers of AI research to demonstrate that the intentional suicided of HAL, the onboard computer in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, was a case of “instrumental convergence,” which is nothing less than Lacan’s all-purpose torus of Seminar XIV, The Logic of Phantasy.

Assignment: Read “Try and Fail,” an introduction to the state of topology in Lacanian studies and a program of the zoom discussion.

Agenda: A pre-trial discovery motion, in the form of an AGENDA of possible discussion topics, is now available.

Optional: See what happens when a key historical distinction (between semblance aphasia and contiguity aphasia) disappears in favor of clinical precision, losing a generation of work on metaphor, metonymy, and critical pathology — which was responsible for nothing less than the birth of structural linguistics. This dialog between Kunze and ChatGPT has several good suggestions for aspiring topologists who would like to see Lacan’s formula for metaphor in a new “toroidal” light. Those fearless topologists who can put up with a 50-minute argument comparing symmetrical difference to the fundamental polygon, sexuation, and instrumental convergence are invited to watch Lacan to the Limits on YouTube.

US East Coast time: 12:00 noon / London GMT 5 pm

Berlin/Italy Central European Time 6 pm

Tehran 8:30 pm

Pass Code: tZ&g1$*3

• No lecture, minimal screen-shares, 2 hour maximum duration •

(Suggested topics, not however limited to this list)

extimité

anamorphosis

isomeric points

katagraphic cuts

cathesis • cathetis

tesseræ

instrumental convergence

Audouard’s thesis

Ames Window Illusion

Lacan’s chess-game analogy

Parrhasius’s curtain

Simonides invention of artificial memory

HAL’s suicide thesis

symmetrical difference

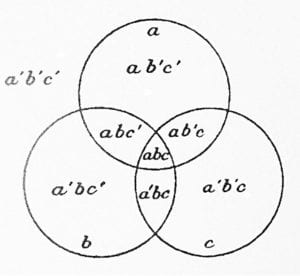

Euler circles vs. Venn diagrams

aphasia and metaphor theory

Freud’s parapraxis

fundamental polygons

discourse theory

thaumatropes

First Zoom Session

Dialog 1: The Neighbour

With Lorens Holm and Andrew Payne

Sunday 02 July 2023 • 12:00 noon (EST) New York • 5:00pm (GMT) London

This is the first in a series of dialogues involving participants in the iPSA book project. Lacan ┼ Architecture is a collection of ten essays by authors with long histories of engaging psychoanalysis in their architectural research. Authors of this collection will treat the spaces of Lacanian subjectivity from a variety of perspectives, in a series of in-depth extended essays. The first session, led by Lorens Holm (University of Dundee) and Andrew Payne, engages with “Introduction to the Thing,” the first group of sessions in Lacan’s Seminar VII, The Ethics of Psychoanalysis (1959–1960).

- Pleasure and Reality

- Rereading the Entwurf

- Das Ding

- Das Ding (II)

- On the Moral Law

The zoom will be an informal open discussion of these and other topics touching on the architecturally central issue of neighbors and neighboring, stemming from Freud’s famous response to the Commandment, “Love Thy Neighbor.” As Kenneth Reinhard wrote (“Freud, My Neighbor.” American Imago, vol. 54, no. 2, 1997, pp. 165–95), “Lacan takes up the topos of the neighbor as the primary particle of ethical theory and traumatic experience left over from the dialectics of God’s death into modernity; the neighbor embodies both the remnant of Judaism in its Christian sublation, and of Scripture in its literary and philosophical secularizations. Lacan ‘s reading of the neighbor separates ethics from both the Kantian autonomy of ethical maxims and the modernist hermeneutics of suspicion that finds all moral systems ideologically compromised.”

iPSA members and guests are invited to weigh in on this most urban of architectural issues and most Freudian of Lacan’s interests in ethics.

Andrew Payne has remarked, in “The Nebenmensch Thing,”

What Saint Martin does not account for here is that in the other which escapes identification. He does not know what the other wants. …

The notion of Nebenmensch thus associates two features of the other: his or her ability to hold together as a nucleus irreducible to its attributes and his or her allergy to analogical identification on the basis of my experience of my own body. One among several noteworthy features of this discussion is the way that it flouts the familiar distinction between persons and things. Here the other person serves as the very paradigm of that Thing that persists behind or beyond the attribution of any personalizing property or predicate and in imperious indifference to my solicitations and remonstrations. What might be at play in this subversion of our customary distinction between person and thing?

Calum Neill has written about the case of St. Martin’s cloak, addressing Freud’s singular objection to what most Christians regard as the summary of the Ten Commandments. There is no actual commandment, “Love Thy Neighbor,” although in Leviticus 19: 18, we find “You shall love your neighbor as yourself.” And, in Matthew 22: 37–40, we read “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets.” Reference to St. Martin’s cloak can be found in Lacan’s Seminar VII, The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, 186.

Neill summarizes:

(page 150) Lacan presents the example of Saint Martin in the context of discussing Freud’s ‘horror’ in the face of the commandment to love one’s neighbour. As we have seen in Chapter 7, Freud rejects the direc- tive to love one’s neighbour, protesting that such a directive runs counter to reason. It is reasonable, in Freud’s perspective, to love those closest, those with whom one can identify oneself. The directive to love one’s neighbour would constitute an affront to those who would be deserving of love and, in so doing, an affront to the subject and the love he would hold precious. What, according to Lacan, Freud misses in this protestation is the ‘opening on to jouissance’ that the encounter with the other would offer.

(page 152) As Lacan illustrates with the example of the story of Saint Martin, the good one gives towards the other, insofar as the other is imagined as the counterpart of one’s own ego, is liable to be the good as one conceives of it for oneself. Saint Martin encounters a beggar one winter night as he is entering a city. The beggar stops him and asks him for alms but, as Saint Martin has no money, he can only give what he has, his cloak. So, he takes his sword and cleaves his cloak and gives one half to the beggar. For Lacan, this example, which might be held in the Christian tradition as the epitome of loving one’s neighbour, actually says very little. The good that Saint Martin takes to be the good of the beggar is nothing but his own good transposed onto the beggar, a point attested to in the story by the fact Saint Martin keeps one half of the cloak for himself. The other as conceived on the basis of its identification with the subject’s own image of itself, its ego, leads to the good of the other being similarly conceived on the basis of the subject’s misconception of its own good.

(page 153) What Lacan is pointing to here is the fact that it is not a question of an either/or. That Saint Martin sees the beggar as wanting or needing clothing to stay warm is not necessarily a mistake. The beggar, in all probability, was quite grateful for the cloak. The point is that this does not exhaust the beggar’s desire, there is, beyond that in the beggar which can be recuperated by Saint Martin, something excessive, a desire which cannot be reduced to the services of goods, i.e. jouissance. This conjunction of goods serves to illustrate the error Freud commits in assuming that the other is evil and harmful. The good one assumes for oneself, the object which would satisfy, serves to safeguard against the encounter with unbearable jouissance. In imputing this good to the other in an exclusive fashion – that is, as the Good – the subject would necessarily fail to account for the fact that this good was never the good for them, but only ever a surrogate and, thus, necessarily not it.

.